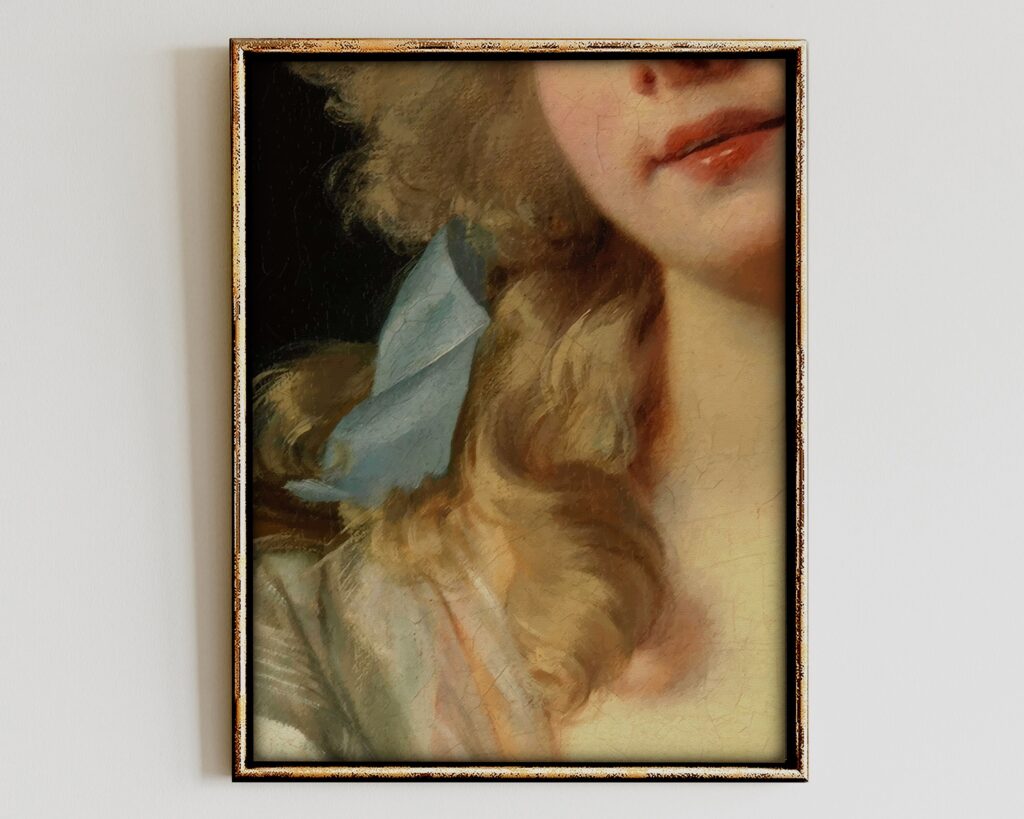

Imagine standing in front of a painted portrait of a Victorian woman, her complexion pale and flawless, framed by soft waves of carefully styled hair. Her cheeks are delicately flushed, and her lips are painted with a shade of rouge that adds a subtle, refined vibrancy. The artist has captured not just her appearance, but the identity she wishes to project—elegant, composed, and dignified. Now, you raise your camera and take a photo of that portrait. Why? What does this second act of creation mean?

Here’s the paradox: the portrait was already complete. It captured not just her face, but the narrative she wanted to tell. When you photograph it, you’re doing more than duplicating—you’re adding a new layer. Your photo has your shadow, your angle, your choices. It’s not her story anymore; it’s your interpretation of her story. You’ve filtered her essence through your lens, and in doing so, the image becomes as much about you as it is about her.

Makeup is no different. Every day, we create our own portraits. A swipe of lipstick, the soft contour of bronzer—these aren’t just tools for enhancing appearance; they’re acts of storytelling. But here’s the twist: the way others see us is always refracted through their own lenses, shaped by their own narratives. Like the photograph of the portrait, our makeup is interpreted, layered and cropped with meaning that might not even be ours.

When you take a photo of a painted portrait of someone wearing makeup, you’re capturing two identities: the one she intended and the one you perceive. It’s a powerful metaphor for human connection and misunderstanding. We’re all walking portraits, painted with intention but inevitably reframed by those around us.

So here’s the question: What do we lose, and what do we gain, when we attempt to capture someone else’s story through our own lens? Whether it’s makeup, art, or how we interact with others, are we truly seeing them—or only reflecting our own view onto their carefully painted surface?